As I mentioned in my last post, when I first arrived in Paris, I was a little freaked out by how inadequate my French was. Even after five years of high school French classes and a bachelor’s degree in French literature (with honors, even). I mean, surely that should be enough!

After I arrived in Paris, I thought it might be interesting to take classes in French (rather than on French) on topics that interested me. So last spring I enrolled in a class on illustration offered in the adult education curriculum of the City of Paris.

Many years before, I had read David Sedaris’s “Me Talk Pretty One Day.” I think I had dismissed his horror stories of the French education system as him being a neophyte. I mean, I had a degree in French literature, so surely my experience would be better!

Um, well, maybe not so much. What I had failed to factor in was that all of my high school and college classes had been geared toward people who had learned French as a foreign language.

So even though the lectures in my Paris classes were in more or less proper French, the professors were still speaking (in their heads at least) to a native French-speaking audience.

And then I probably should have paid more attention to the fact that, during the first class I took this past spring, the illustration professor lost her sh*t when another professor seemed to be scheduled for the same classroom and started yelling at him.

Or when she made one of the other students cry, also in the first class, I don’t really remember for what, but you can imagine. Apparently there were a bunch of complaints from the other students following that incident, and a survey was sent out, and there was a monitor at the next class. But for whatever reason, I’m not sure why, I decided to tough it out.

I had thought than in an academic setting, I would be able to understand pretty much everything. And I did understand a good chunk of what the professor said (though definitely not all), but then when the other students would pipe up, I understood practically nothing.

Compared to the other students in the class, I was competent but definitely not inspired. I did manage to make a decent drawing of a pigeon during one of our excursions to a park a block away from the school. The assignment was to draw in INK (I was used to sketching in pencil, so this gave me the willies) by first watching and then drawing from memory with our LEFT HAND and to capture its MOVEMENT. This one turn out fairly good, I think. The other ones, not so much.

In the end, though, I decided that illustration was maybe not my forte.

So this past fall, I decided to enroll in a class that was a bit more along the lines of what I’m reasonably good at, a class on the History of Contemporary Photography. I had taken a number of photography classes in the University of Washington’s adult education program and at the Photographic Center Northwest in Seattle, and I thought it would be good to get a better understanding of contemporary photography and that it would be interesting to see that from a French perspective.

Which it was. After all, the French actually invented photography, and two of the streets in my neighborhood are actually named after earlier pioneers in photography (rue Niepce and rue Daguerre). The class was an interesting mix of French (Eugène Atget, Marcel Duchamp), Franco-American (Man Ray, Berenice Abbott), American (Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Diane Arbus, Barbara Kruger, Gregory Crewdson), Canadian (Jeff Wall), and German (August Sander, Hilla and Bernd Becher, Otto Steinart, Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff).

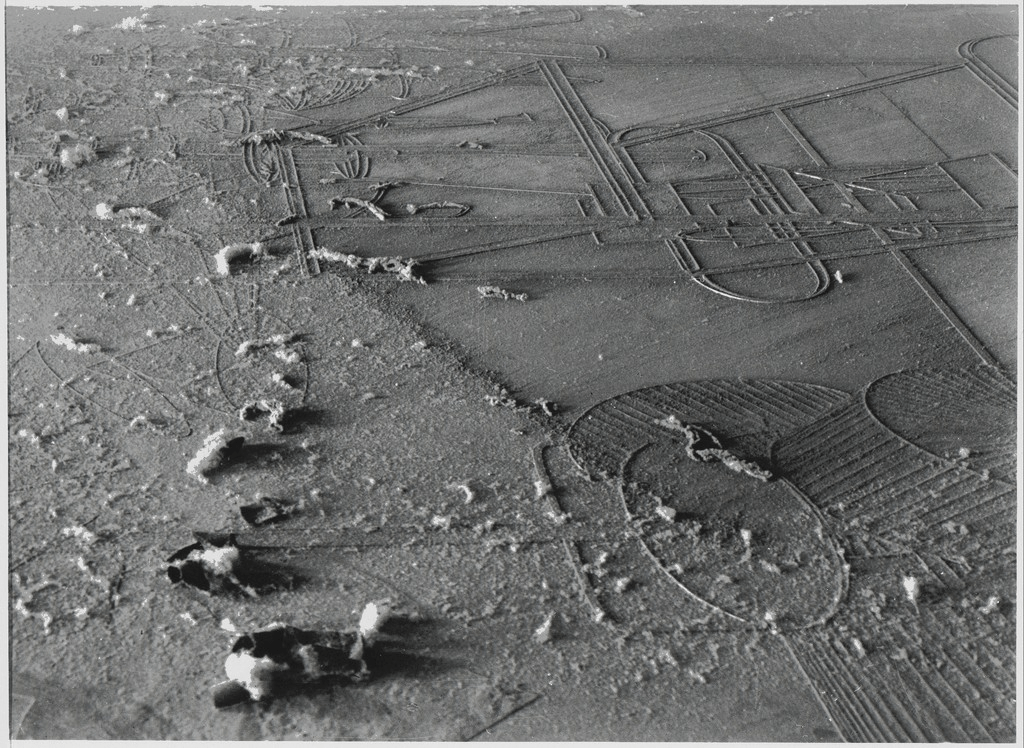

This is Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray’s “Élevage de poussière” (“Dust breeding”) from 1920, an early use of photography to capture an ephemeral work of art…

Nevertheless, the class was oddly dry and was heavy on “talking points” about the various photographers and schools. Each class would begin with the professor prompting students to provide a recap of the previous lesson. The discussions on the photographers were focused on biography and didn’t provide much illumination on their philosophy and technique.

At one point, the professor made a point that one photographer’s framing was exceptional. One of the students asked what made their framing exceptional. The response was, “Well, you just have to look at the photographs!” Buzz. Wrong answer. I wanted to understand their motivations, their process, their techniques. This was not helpful.

For this spring, I looked at the options for classes to take, but nothing really grabbed my eye. And then after a moment I realized, the class I really needed to focus on was my driving class. Not sexy or even very interesting, but necessary. My Washington driver’s license was no longer valid in France as of September, so if I wanted to be able to drive in France, it was a must.

There’s kind of a weird thing with French driver’s licenses, though. There are a bunch of US states that have reciprocal agreements with France that they can exchange driver’s licenses. Meaning, that if, for example, you have a Pennsylvania driver’s license, you can exchange that for a French driver’s license with no fuss.

Washington is not one of those states. So in order for me to get a French driver’s license — mind you, that’s only so that every once in a while I can rent a car and drive off into the French countryside where the trains don’t go — I have to go through the whole French driver’s license process as if I’ve never driven a car in my life, like I’m a sixteen-year-old. Ugh!

In France, to get a driver’s license, you first have to pass the written test, and then you take a minimum of twenty hours of driving lessons, and then you take the behind-the-wheel test.

I took practice written tests, and even after reading the codebook from cover to cover, never managed to pass. Yikes! I will say that the French written test is considerably harder than the American one, with questions like, if you’re traveling at 50 kilometers per hour, how many meters does it take you to stop? (The answer is 25 meters — you take your speed, lop off the zero, and square it. Like that particular tidbit of information actually does you any good.)

And then there are all the French road signs, which in many cases can be quite different from American ones. Like this “no pedestrians” sign…

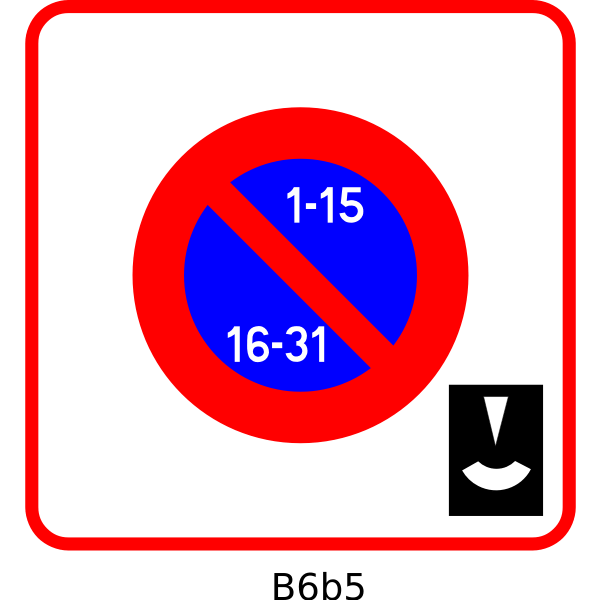

Or “no parking”…

Or the fact that at an unmarked intersection, you have to yield to cars coming in from the right. Which can also be marked this way…

Or the signs that indicate you can park on one side of the street during the first half of the month, and then on the 15th between 8 pm and 9 pm, you have to move your car to the other side of the street, and then move it back between 8 pm and 9 pm on the last day of the month — a whole concept that does not exist in the US…

And they expect you to know all these things. None of which were covered in my nine years of French classes.

And then lastly, I probably mentioned at some point that at the beginning of 2023, I joined a book club at the Paris LGBTQI+ Center. For the first six months or so, we met at the Center, and then shifted to meeting at the apartment of two of the members, Linh and Robyn. All the other members are folks in their twenties from across the LGBTQI+ spectrum and from a variety of backgrounds. And in the past few months we’ve expanded our scope to also watch and discuss films together.

Typically an evening will run like this… We show up at Linh and Robyn’s carrying supplies for l’apéro, basically snacks, wine and other beverages. Their apartment is, I imagine, fairly typical for French twenty-somethings with its somewhat crowded mismatched furniture, bookshelves overflowing with books and manga, posters plastering the walls, a tiny kitchen.

We settle in on the sofa or cushions set on the floor or on the mismatched chairs, trying to avoid knocking things over. We talk about everything and nothing while setting out the snacks, which usually include various types of chips, several baguettes, things to smear on the baguettes like soft cheeses, hummus, guacamole, etc. A bit of wine, soda, fruit nectar, that sort of thing.

Once everyone arrives, we eventually get around to discussing the book, things that we liked or didn’t, passages that spoke to us or that maybe we didn’t quite get. This goes on for quite a while of course.

And eventually Linh hauls out her laptop and we select our next book and/or film from the ones that people have proposed and that she tracks on her Excel spreadsheet. And clean up and exchange hugs and bisous and head out. Usually the whole thing lasts around four or five hours, maybe six.

This past weekend we had one where we discussed a memoire by Catherine Patris, a doctor who led the AIDS Division at France’s Ministry of Health from 1993-1995 , called “Ma planète SIDA” (“My Planet AIDS”). Linh had met Catherine at the LGBTQI+ Center and had invited her to join our group for the discussion.

The book speaks of her struggles, her moments of fierce pride for what she was able to accomplish, the human connections she formed with people also engaged in the fight against the disease. It talks of her efforts to stay on top of the rapidly evolving medicine and the state of the epidemic, to transform the division from a cold bureaucracy into a one where human emotion and passion had a place.

She recounts the difficult negotiations with the Ministry of Health’s leaders to act more quickly and more boldly, with activist organizations like ACT UP, who stridently criticized the AIDS Division for not acting more quickly and more boldly. Of the frustrations with being caught in the middle.

She tells of meetings where, as she looked across the room, it struck her that most of the people sitting there would not be alive within in a year or two.

So after reading all this, it was amazing to be able to meet Catherine herself that afternoon, nestled into Linh and Robyn’s sofa. Catherine and I were the only ones in the room to have experienced the AIDS crisis firsthand, even if from different vantage points.

There were points during the discussion when everyone was laughing together, others when everyone’s eyes were wet, hers included.

She talked about how the real problem is shame, and the reason discrimination is so problematic is because it induces shame. And that the only cure for shame is kindness (“Le seul traitement pour la honte, c’est la tendresse”).

On the way home, I ended up taking the same métro train as Lu (far right in the photo). He/they said it had felt like a family dinner, which the French traditionally consecrate their Sunday afternoons to. And I certainly felt a bit like, here and elsewhere, I’m starting to find my family here.

OMG the drivers license problem seems insurmountable. Will that change when you have French citizenship? Your book/film group evenings sound delightful! So glad you are blogging again!

Thanks, Libby! For the drivers license, I’m cautiously optimistic that I’ll be able to pass the written test, though it might take a few tries. 😁